It is generally accepted on https://telegram-store.com/catalog/product-category/channels/economics that it was in Babylonia in the seventh century BC that the first banks appeared. They were called business houses and performed credit and debit functions. For example, they gave money loans at 20% a year to all creditworthy citizens, accepted monthly installments, provided for the needs of international trade, financed the army, collected taxes and supported the needs of the government.

A century later, Babylon’s banking system evolved to such an extent that there were analogs of the first checkbooks in the form of clay tablets. Bankers recorded data on two “documents”: the first was a receipt and the second was a “check” to bearer.

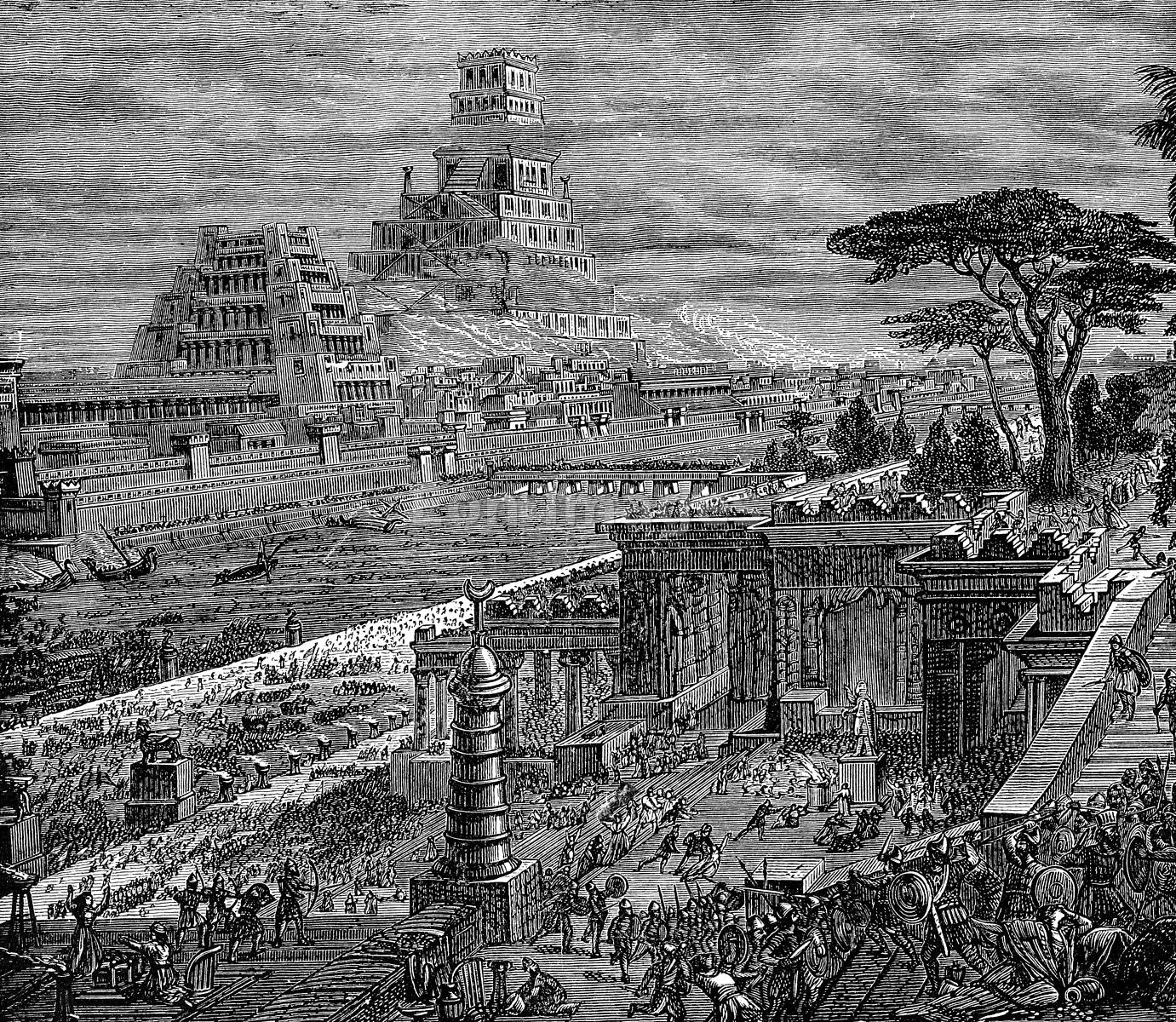

19th-century illustration, “Capture of Babylon.” The forces of Persian king Cyrus the Great (AKA Cyrus II) capture the city of Babylon in 539 B.C.

Perhaps the most famous Babylonian banker was Nabu-ahkhe-iddin, who lent money to King Belshazzar. Nabu-ahkhe-iddin was also the first private usurer of whom history has preserved records.

The son of a merchant who inherited only debts from his father, Nabu-ahkhe-iddin worked as a scribe to give all his earnings to his creditors. Having paid his debts, the future banker made his fortune and started to give loans himself. Houses, slaves or grain served as collateral.

If the borrower could not provide a guarantor or collateral, he received a loan at enormous interest rates of as much as 40% per annum. After the death of the first private banker, his descendants increased their capital many times over, surpassing the wealth of the largest temples of the time. The most wealthy merchants of the ancient East entrusted their money to the heirs of Nabu-ankhe-iddin.